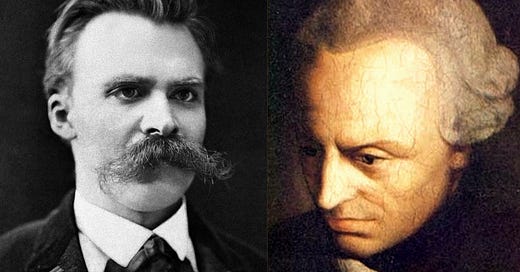

When I was a sophomore and thought like a sophomore, I loved Nietzsche most of all the philosophers.

It was an uncomfortable love because I didn’t care for the Will to Power as a way for me to exert myself, instead, I just adored his Genealogy of Morality, in particular the dissection he has of the Priestly class and the way some people use self-negation as a means to power. I loved it precisely because I hated St. Augustine and the self-righteous people I’d grown up around.

Nietzsche presented me the opportunity to think through the hypocrisy of all the people I didn’t like growing up and taught me some interesting ways of considering morality as a human system of thought instead of a plan imposed from on high.

Like many sophomores, I thought Nietzsche gave me all the tools I needed to be free in the way I needed to be free. I was not a blond beast, nor am I an Ubermensch, but I was a person sickened by many of the pieties around me.

I loved Nietzsche because he allowed me to kick at everything I found disgusting.

***

Kant made too much sense. I understood from my own mind that there were demands the world placed upon me because I was a part of it. The potential of my owing so much to the world scared me. I could not handle being obligated to so many people, to so many ideas.

But at the same time, I have often felt the pull of the ideal. I do not, in my heart, accept pure materialism as the basis of the world. I also do not accept that we are pure individuals. We have individual rights, but we do not exist within the world freely. We are born with ties and we accept more of them.

Kant poses the difficult question of whether breaking those chains in pursuit of our individual wants and heroic urges makes us more free than seeing our bonds not as cold links but the net upon which we walk. Kant believes we are more free in fulfilling our obligations than in satisfying our desires precisely because the principles which drive us to do right to others are more durable than any fleeting want. The real chain is the one leading you around by the nose making you prove what an Ubermensch you are.

***

A very bastardized form of Nietzscheanism bestrides the world these days, bullying everyone. Instead of seeing the exhortation to go beyond good and evil as a seeking for the ultimately productive, some people have seen it as endorsing a complete rejection of the ethical altogether.

We are only beasts wrestling for dominance, these folks seem to say, and all that matters is you come out on top. They will gesture towards ideas of Slave Mentality while behaving much more like Nietzsche’s ressentiment-addicted Slaves than his Masters.

Kant’s cosmopolitanism is on the wane, viewed suspiciously from many corners as too weak, too mealy-mouthed. Sure it has a categorical imperative for everything but how is it helping make the world more human. How can such a mechanistic ideal of interlocking promises produce the world we need.

We are all such particular identities we cannot all be ruled by the same imperatives. We are not citizens of the world. We are ourselves alone.

Yet no hero stands up all on their own. Achilles had Patroclus, Odysseus had Athena, Aeneas had Venus (and Dido and Jupiter), oh yeah, and whole armies. And the next time you encounter someone asking for a great culture hero, someone making the sacrifices necessary to heal the world, I would recommend quoting them Achillies: “It is better to be a slave on earth than a king in Hell.” Just to say, the pleasures of the flesh aren’t why Achilles says that—he doesn’t just miss Patroclus’ arms or the joys of Mutton stewed upon a tripod. He misses the ability to love with consequences.

The thing Kant gets so right is that time is our greatest asset because time is endless. He couldn’t have known it, but General Relativity correctly describes time as a dimension, and there is absolutely no way for a dimension to be destroyed. Every moment that you make lasts forever. Until the fabric of spacetime is ripped apart, the everything you’ve ever done or will do will endure, recurring endlessly.

What would rather have the sum total of your moments look like: running around after whatever desire you can conjure for yourself or working to improve the lives of those you love?

I guess science does provide a basis for philosophy, the categorical imperative in particular.

Still, Kant’s wish for world ties looks quaint in the internet age. Here were are, all literally connected by invisible bonds, on the whole much wealthier than before, on the whole more republican, and many of us hate each other.

But being outside the zeitgeist—to mix my Germans even more—is not to be wrong, and it is, in its own way, to summon the spirit of tomorrow.

For soundtrack I invite you to listen to this, this, and this all at the same time.

***

The world beaters keep wanting to say the principle of perfection will save us. Nietzsche said once that the goal of all society is the creation of exceptional men who will drag the world into the future.

No one needs to worry about inequality in that world, since the little people don’t matter anyway, except as fodder for the great ones to feast upon.

Still, as a counterexample, just for fun, one might point to good ol’ Napoleon. That man of destiny would never have amounted to anything if the Revolution hadn’t destroyed old systems of inequality to make advancement on merit viable. But you might say these men are not concerned with creation of men of destiny (I’d call you a liar but okay), they are concerned with making great economies—which are created by great men. To that I would point to Rockefeller and Ford. These two great White Antisemites were pulled out of poverty because they relied on the relative equality of the oil business at its beginning and the potential for failures to try again.

The economy might run on structural inequalities—literally the difference between supply and demand—it is fundamentally built upon human consumption and human needs and human striving, and the advancement of those human qualities is better forwarded when all people have equal, fair opportunity to advance, learn, and develop.

All markets rely at bottom on humans, so when we draw—just a sidenote here—antagonisms between state limits on technology and market limits on tech what we are doing is creating a false dichotomy between various forms of human decision-making. The state is there to put the value of citizens as a whole first—regardless of whether it does—and markets to put the value of its members as a whole first—regardless of whether it does—so to claim one or the other is a better arbiter is to miss the bottom reality of both: they are different stores of human knowledge, neither can be the only deciding factor on technology.

All of that’s why AI could be great and terrible. AI can make the mediocre above average and allow for educational specificity for individual students, but AI also has no human obligations.

The economy, the state, relationships, life are all vast webs of human duties, obligations, and ties, so what I worry about is that the bad “Destiny men” will try to supplant the real base of the economy—and life—with an artificial alternative.

Much like with ideas of virtue, the hard limits of the economy and its basis in human interaction are what give it meaning.

***

Yet Kant has one concrete knock against him: He can be hard to read. He doesn’t speak in pithy or cryptic aphorisms one can quote to feel important. He writes long, complicated sentences which take a magnifying glass to untangle and interpret correctly, which in a way is the core of their fun and reflect his desire to reconsider how to consider in the first place, but which for the average reader (or, let’s be honest TikTok scroller) are little more than an alphabet gumbo, but which for the trained reader reveal deep truths they can be even more self-important about than knowing an obscure aphorism.

To most: fuck that.

And the problem of educational polarization is real. The over-educated and the less-educated speak and live in different languages, and the over-educated can get lost in their own self-constructed labyrinth.

But just as big words do not mean big emotions, short sentences do not ensure clarity.

Nor does popular rage.

The populist pushback from left and right against cosmopolitanism and its supposed decadence arises from a desire for moral clarity on a grand scale and greater license on the micro. The most dedicated “populists” want to re-valuate the big values but do not want to be bound by the rules.

Moral clarity is not moral rightness.

The rules and principles of human interaction are too complicated to be easily rendered into slogans. I reject populism on the grounds that it doggedly goes after one particular goal—appeasing ressentiment—at the expense of all others. It may have shaken loose certain members of our elite from their monomaniacal goal of amassing as much money and power as they can possibly fit in their fists, but that could have occurred via a widely-based sense of real cosmopolitanism.

That is my plea—return cosmopolitanism as our ideal. No single point of view can distill the world into comprehensibility, and we must accept this truth.

Respecting our obligations to each other does not require demur decorum nor a single way of thinking and acting. Our national slogan is not ab unitate virtutis but e pluribus unum. Our strength is our multiplicity and our mutual bonds.

***

The older I get the more I find people I disagree with. I used not to believe in the reality of evil. That has changed.

I used to believe in strict equality—all people with equal abilities and equal dreams—and Nietzsche, whether you believe it or not, was part of my justification for that faith. I believed all people could achieve themselves.

I now have more ties and more experience. We are not all equal in talents. We are not all equal in drive and understanding. We can choose to do evil to each other.

But none of these disillusionments have soured me.

We owe each other our lives, and in that owing we are human.